In 1937, with the deregistration of the Singapore India Muslim Society and inactive trustees, an abandoned mosque was about to get a new lease of life. Before World War II, the Malabar Muslim Jama’ath stepped in to manage the mosque at the Kampong Glam Muslim Cemetery, appointing an imam to lead prayers. In 1952, C H Abdullah, an influential figure and Malabar Muslim Jama ’ath President, initiated repairs and expansions. A year later, plans were underway to build a new mosque to replace the original one, which would become the city’s second largest mosque at that time.

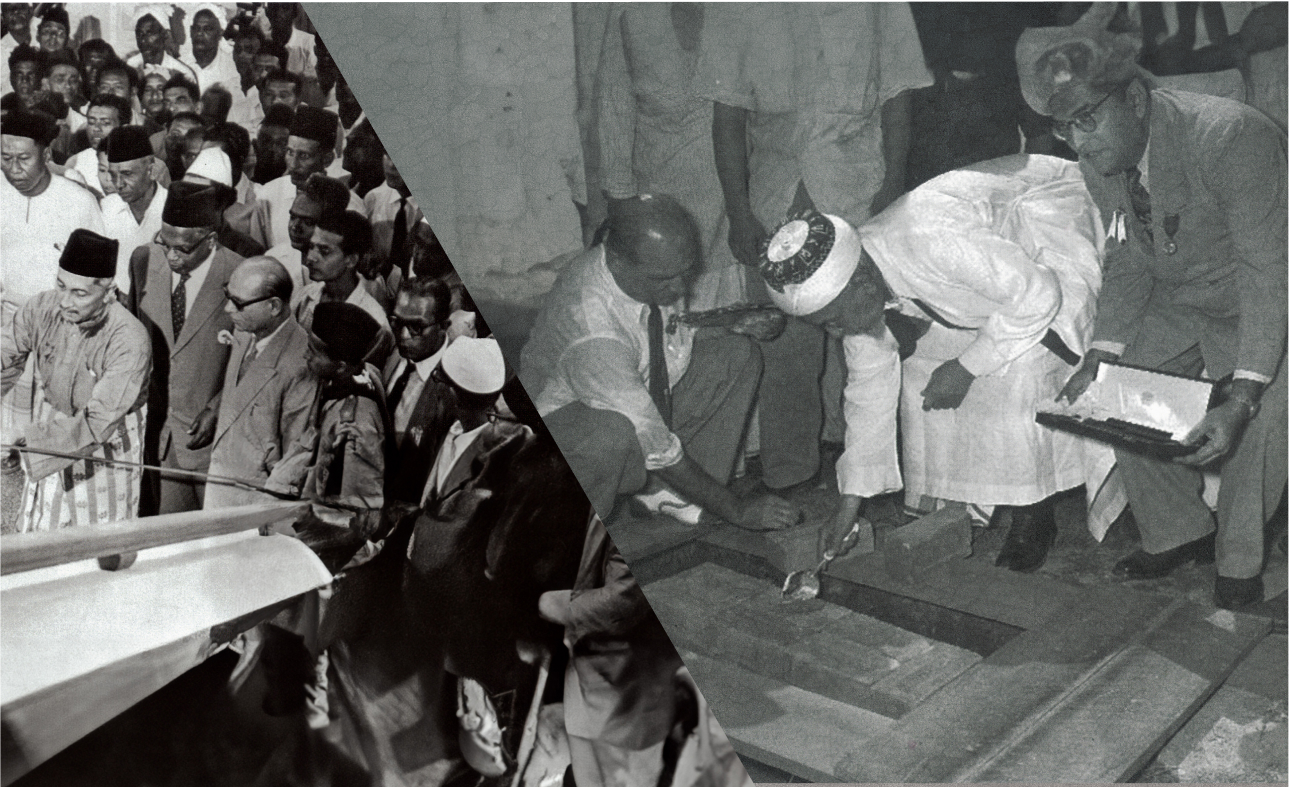

On 10 April 1956, the Mufti of Johor, Tuan Syed Alwi Adnan, laid the mosque’s foundation stone. Then, on 24 January 1963, Yang di-Pertuan Negara, Yusof bin Ishak, later Singapore’s first President, declared Malabar Mosque officially open.

While embracing Muslims from diverse backgrounds, the Malabar Mosque proudly preserves its Malayalam identity with the delivery of Friday sermons in Arabic and translated into English and Malayalam. The Urban Redevelopment Authority recognised the significance of this heritage mosque and conserved it in 2014.

In 2023, further enhancements to Malabar Mosque were made under MUIS’ Mosque Upgrading Programme. An extension was added to accommodate a larger congregation and an increasing number of students for religious classes. Its capacity nearly doubled, accommodating 1,000 people at a time.

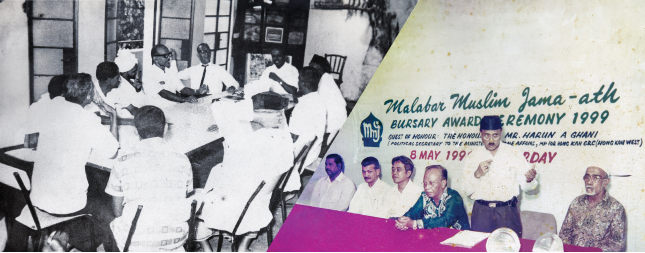

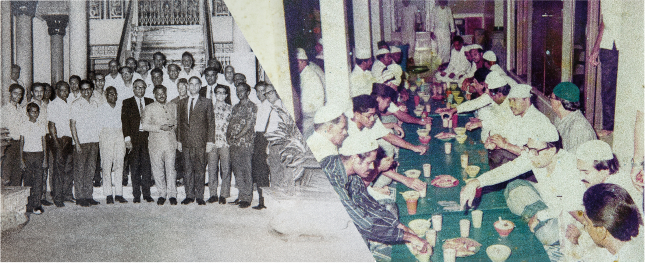

As early as 1822, community organisations were formed based on origins, surnames or language, providing social, religious and economic support to fellow migrants. The Malabar Muslim Jama’ath (MMJ), a non-profit organisation, was registered on 12 December 1930. They played a crucial role in fostering a sense of community among Malabari migrants and providing the poor with meals. Religious observances, such as commemorating Prophet Muhammad's birthday at the Malabar Mosque, held great significance for MMJ members and were held even during the Japanese Occupation in 1943.

Today, more than 90 years after its formation, the MMJ continues with its core activities centred on faith, community service, and building family and community bonds. First launched in 2012, the Give Ramadan charity drive is an important annual activity for MMJ’s members, bridging ethnic and religious boundaries to support those in need regardless of race or religion. During the fasting month of Ramadan, MMJ distributes bags filled with essential food items to the less fortunate.

It is a longstanding tradition of the MMJ to build bonds of friendship both within different segments of society and among its own members. In recent times, the organisation remains accessible to members and the public through its online channels such as the MMJ website, Facebook and YouTube videos. Today, the organisation’s enduring legacy lies in the revitalisation of Malabar Mosque and the cultivation of a vibrant community at the mosque, fostering unity among its members.

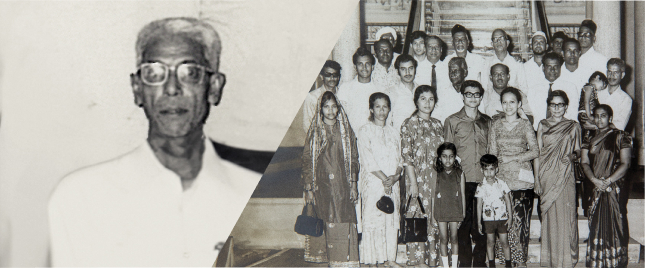

Malabar Mosque is known colloquially by some as the Blue Mosque of Singapore as its façade is covered in striking blue tiles. Since the 1950s, many people, including Malabari ice-ball vendors, joined forces to raise funds for the mosque’s construction. Many mosque management committee members, including Haji Osman bin Abdullah, had also overseen significant fundraising and renovation efforts for the mosque.

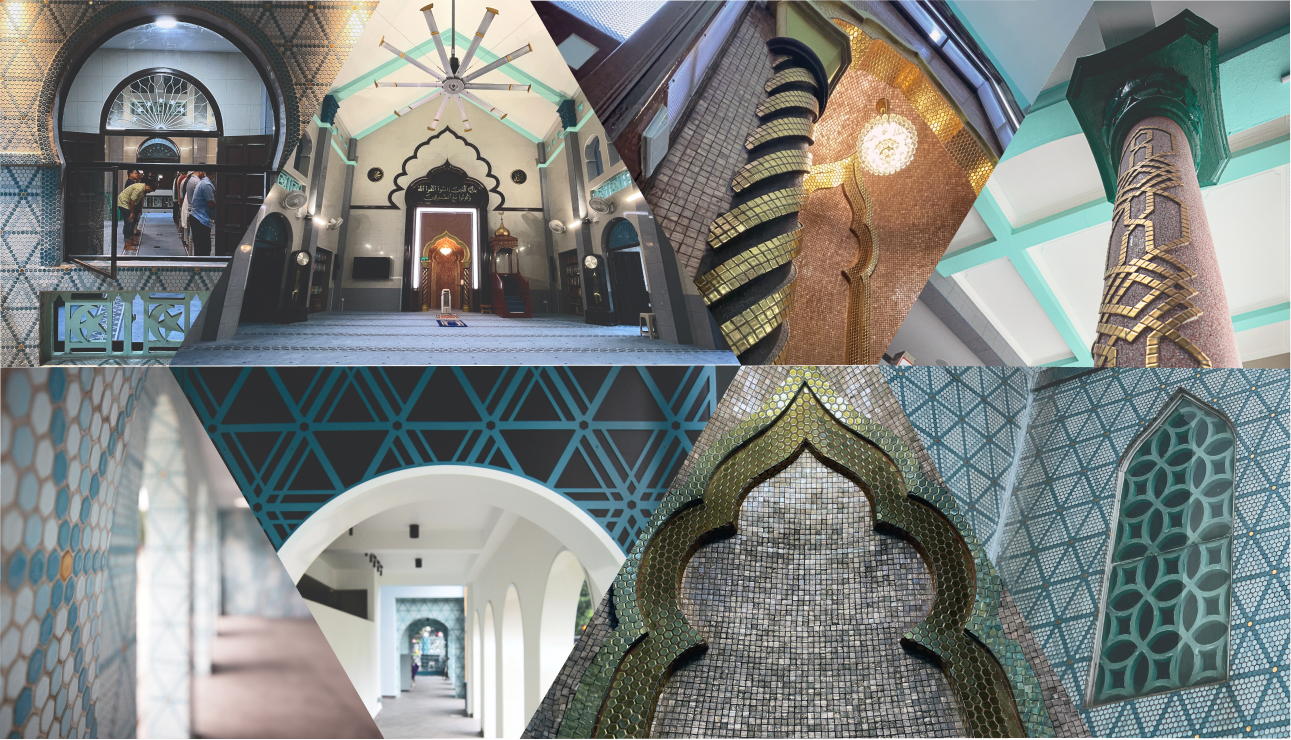

Officially opened in 1963, the mosque was designed in a traditional style and featured an octagonal tower topped with a golden dome. The mosque underwent a renovation, completed in 1995, that saw the addition of blue and white lapis lazuli tiles to its interior and exterior walls. Malabar Mosque’s new entrance—a grey and golden archway links the traditional main mosque complex, built in 1963, with the new annexe, completed in 2023. Reposeful blue, white and gold hexagonal mosaic tiles grace the exterior and interior of the 1963 main building, with these colours replicated in the new annexe building.

With the completion of tiling works, Malabar Mosque had symmetrical patterns in blue and white, reminiscent of mosques in Pakistan and Iran. The architecture reflects a combination of Saracenic, Mughal and Singaporean influences. Symmetry plays a vital role in integrating the traditional and modern aspects of the mosque. In the older mosque complex, coloured mosaic tiles are arranged in symmetrical designs – a common feature of Islamic art. The new annexe building continues this tradition of symmetry with the use of symmetrical blue metal frames, albeit in a modern way.

Within the serene grounds of Malabar Mosque rests Habib Sayyid Muhammad bin Muhammad Shatiri or Kunhi Koya Thangal. His tomb, covered with a simple green cloth, lies behind a silver-painted gate. Considered a saint by many, he frequented the mosque in the late 1940s, offering assistance to those in need. Even after his passing in 1950, his gravesite continues to be frequented by visitors.

Moulana Abu Bakar, became Malabar Mosque’s imam in the 1960s. Through his Thursday night gatherings centred on praising Allah SWT, he attracted Muslims from diverse backgrounds to the mosque, thus making Malabar Mosque a renowned spiritual development centre. He also taught in Indonesia, and was buried in his hometown, Trikaripur, in 1991.

Another respected figure of Malabar Mosque is Haji Osman bin Abdullah. Joining the committee as a teenager in 1960, he dedicated six decades of service to the mosque. In 2009, he raised funds for the mosque’s renovations. Under his leadership, the committee raised over S$6 million for the mosque’s extension works in 2023.

The Malabar Mosque has undergone various transformations over time. In 2023, a new mosque annexe was completed, expanding its boundaries to include the graves of three respected Bugis personalities. They are Haji Omar Ali, his first wife, Hajjah Boosainah Indok Sempoh, and their son, Haji Ambo Sooloh.

Hailing from Pontianak, Indonesia, Haji Omar’s properties were located at North Bridge Road and Jalan Besar, among other places. Known for his generosity, Haji Omar Ali extended a helping hand by offering temporary shelter at his three-storey house at Java Road to incoming Bugis traders arriving in Singapore.

Following in his father's footsteps, Ambo Sooloh was also a successful businessman and community leader. After his passing in 1963 at the age of 72, he was laid to rest at the old Indian Muslim Cemetery at Kampong Glam.

Between the 6th to the 8th centuries, Arab traders arrived in Kerala, introducing their Islamic beliefs and values to the non-Muslim natives of Kerala, shifting the dynamics of its locals.

One of the unique cultural features of Malayalees is the Malayalam language, a South Dravidian tongue closely associated with Tamil, possessing its own distinctive alphabet. However, within the Malayalee Muslim community, a pronounced form of written communication took form, the Arabic-Malayalam. This script continues to be utilised in Malabar Mosque today. The educational curriculum for religious studies revolves around the Qur’an, Islam’s holiest book, and relies on Arabic-Malayalam textbooks to deepen their understanding.

Meanwhile, Singapore Malabaris include those who were born in the Malay Peninsula regions of Penang and Johor. In the 18th century, Malayalee Muslims had already settled in Penang attracted by its status as a free port from 1786. Malayalee Muslims are thought to have participated in Penang’s trade with lower Burma, the southern provinces of Siam and the northern states of the Malay Peninsula.

In 1883, a sailing ship carried the first group of Muslim men from Travancore to Malaya. Amongst them was S M Pareethu Serang, who rose to become a prominent individual in Singapore. In 1922, under a partnership, he formed the Tamil Labour Company to supply labour, servicing the Singapore Harbour Board. Malabari migration to Singapore continued, with some 7,000 Malabaris recorded in 1957. Together with later arrivals, they could be found in the town and the outskirts of Singapore, such as at Sembawang, Beach Road, Arab Street, Jalan Besar and Desker Road.