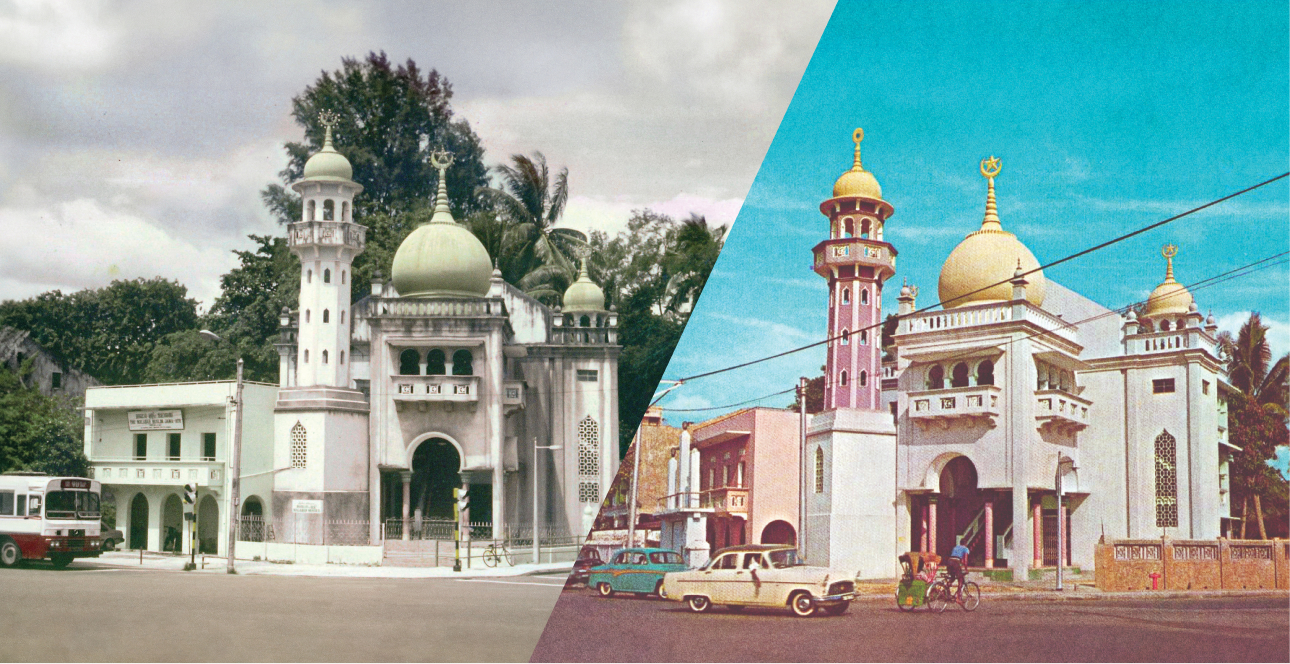

In 1901, Almeida and Kassim, an architectural firm, submitted a plan to construct a mosque within the Indian Muslim burying ground at Kampong Glam. Tengku Ali had previously granted the cemetery to the Indian Muslims for their use. This mosque, under the informal management of appointed individuals, continued to cater to the spiritual needs of the Indian Muslim community.

By February 1909, the mosque and the burial plot gained stronger institutionalised identities. At a meeting that took place at the Singapore India Muslim Society, five men were elected to become their first managers and trustees. In 1910, four of them—mostly merchants—signed a Declaration of Trust. They declared to hold the land and mosque in trust for the Indian Muslim community. Additionally, the Malabar Mosque was designated for religious services and the adjacent land for burial. The following year, a government lease assigned the land and premises to the trustees for 999 years.

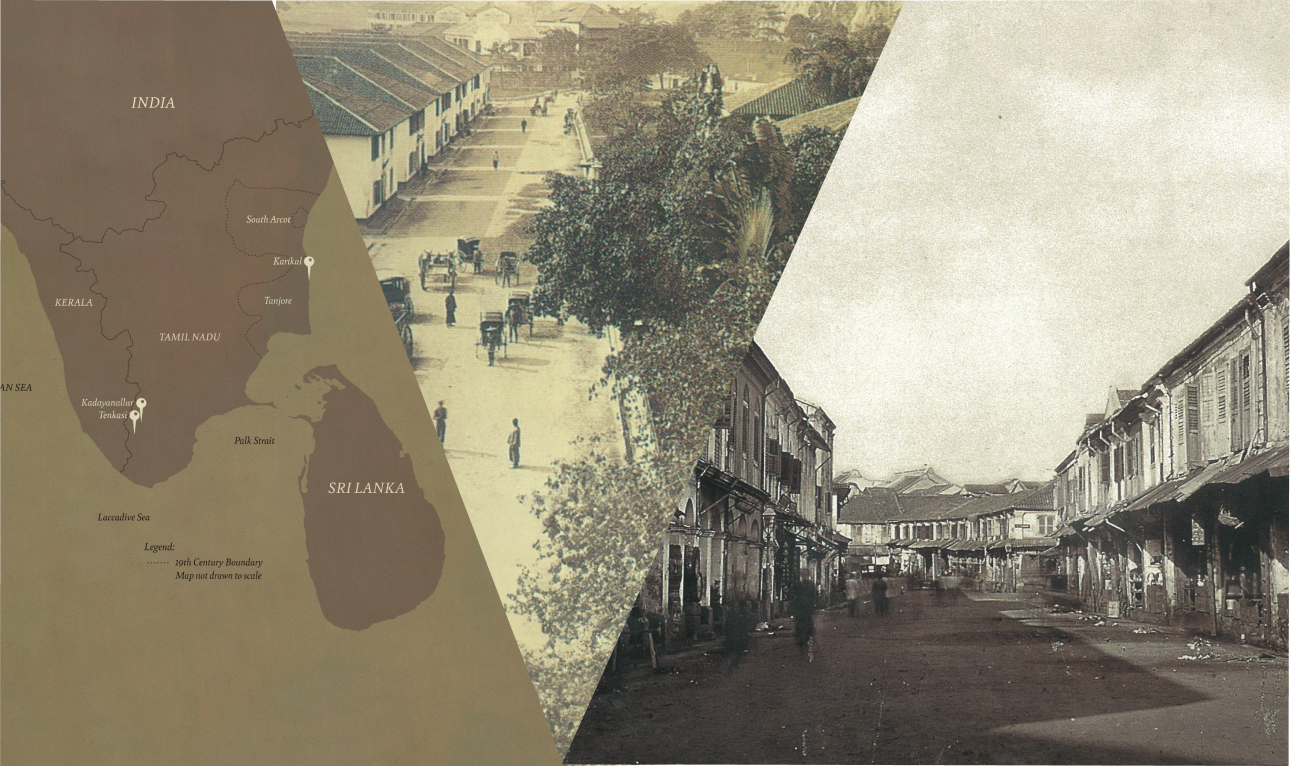

Singapore’s Indian community is diverse, vibrant and rich in language, culture, religion and regional differences. Historically, Indian immigrants first arrived in Penang before settling in the Straits Settlements and the Malay Peninsula. Singapore’s first Indian arrivals included Northern Indian soldiers in January 1819. According to the 1849 census, over 4,900 Indian Muslims accounted for about 80 per cent of civilian Indians in Singapore. Among these early Indian settlers were Muslims, Hindus and Christians.

During the 19th century, Indian Muslims from Tanjore, South Arcot Districts and Karikal among others migrated to Singapore, who stayed in Chulia Street, Market Street, Geylang Serai and Arab Street. These traders of cloth, cattle or gems, moneychangers, provision storekeepers and labourers made valuable contributions. As sojourners rather than permanent settlers, they returned home to India once every few years.

Following World War I, another group of Tamil Muslims, including artisans and weavers from Tenkasi and Kadayanallur, sought refuge from famine and migrated to Singapore. Tamil-speaking Muslims have played a pivotal role in shaping Singapore’s Muslim landscape through their establishment of associations and mosque endowments.

The 20th century migrants lived in areas such as Tanjong Pagar Road near the Singapore Harbour. While the men took on odd jobs as labourers, the women sold ground spices from door-to-door to eke a living. Collectively, the 19th and 20th century migrants set up institutions such as mosques, endowments and a Tamil school. Additionally, Tamil Muslims also set up voluntary associations such as trade and religious associations.

In Kampong Glam, vibrant communities of South Indian Muslims flourished. One enclave, found within Arab Street, Baghdad Street, Bussorah Street and Beach Road, was granted to the residents in 1823, becoming their cherished home. Another group of Indian Muslims settled along the Rochor River, specifically at Kampong Kapur, adjacent to Kampong Boyan.

Kampong Glam became a hub for Malabari and Tamil Muslim businesses. Along North Bridge Road, renowned restaurants established by Malabaris emerged, including Zam Zam Restaurant established by Haji Mahmud in 1908, Victory Restaurant opened by Abdul Raheman two years later, and Singapore Restaurant by C H Abdul Kadir in 1911.

Jalan Sultan showcased the expertise of Indian Muslims in perfumery, money changing, food and textiles– trades that continue to thrive today.

In 1941, Jamae Mosque had both Tamil-and Malayalee-speaking Muslims in its congregation and a management committee that comprised members from both communities.

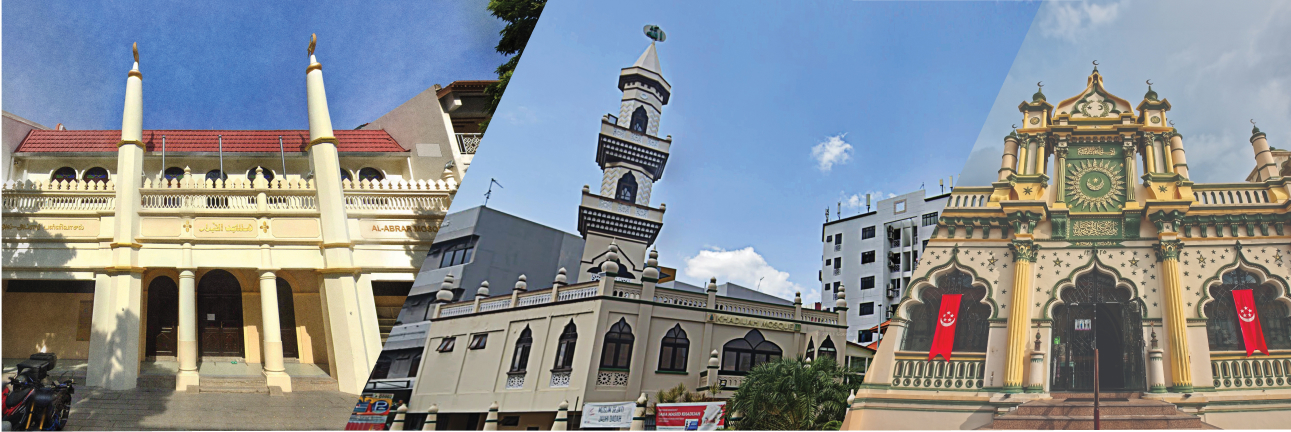

Besides Jamae Mosque, which was built between 1826–27, and the former mosque at the Indian Muslim cemetery at Kampong Glam, Tamil Muslims built several other mosques, including Al-Abrar, Abdul Gafoor, Kassim, and Khadijah Mosques. These mosques were established by traders and merchants and served the religious needs of the Tamil community.

Beyond urban areas, Muslim Malayalees frequented Jumah Sembawang and Naval Base Mosques. It is estimated that 30 per cent of Singapore’s Malayalees, including Muslims, worked at the British Sembawang Naval Base. They were also known as the bicycle brigade. They helped in the establishment of Jumah Sembawang Mosque in the 1920s. The Naval Base Mosque, initially a small prayer space for the dockyard workers, was transformed into a mosque with the assistance of the British in 1968. These mosques had Malabaris who led prayers. Nearby Malabari residents often volunteered there. Jumah Sembawang Mosque closed in 1995, replaced by the larger Assyafaah Mosque, while the Naval Base Mosque was phased out in 2000.

In Singapore, the term ‘Malabari’ refers to Malayalam-speaking Muslims from Kerala, India. It was the Arab traders who played a crucial role in introducing Islam to the native Malayalees and shaping their culture centuries ago. While the earliest official record of Malayalees in Singapore dates to a 1911 census, traces of their presence can be found much earlier. An 1838 newspaper report mentions students from the Malabar Coast at a Tamil school, indicating their early settlement. By 1856, Malabar Street, named after Malabar Coast migrants, had already been established. During this period, Muslim Malabaris had also formed a settled community in Singapore.

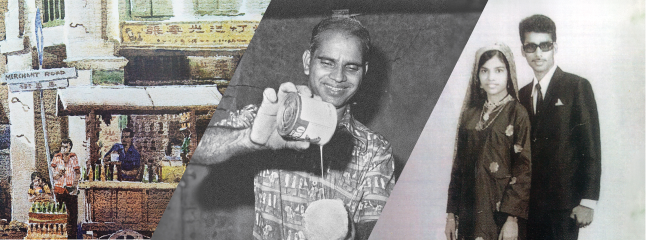

Malabaris were engaged in various occupations. By the 1850s, they ventured into the food business, gaining recognition as ice-ball sellers. In the 1950s, Malabari businessmen managed provision shops or kaka shops across across Singapore, while professionals like stenographers and bookkeepers emerged within the community and worked for the British.

One Malabari who succeeded in a variety of ventures such as the travel agency, money-changing, restaurant and hotel businesses was the founder of ABM Group Holding Pte Ltd, Mohamed s/o K V Moideen Kutty. The philanthropic work he initiated benefits the Malabar Mosque till today.

In 1955, Haji Mohammad Abdul Kadir started a spice business at home. His high-quality and economically priced ground spices, known as 'Malabar Masala,' gained popularity in Indian and Malay households. After his passing in 1963, his sons took over, moving the business to Geylang East in the 1980s. In 2007, the grinding operations moved to Johor due to competition and save costs. Today, the spices are branded as 'Malabar' and are available in Singapore, Malaysia, Brunei, and Indonesia, reflecting their widespread appeal.

In the 1960s, Malayalees formed mini Kerala enclaves in different parts of Singapore. The British Sembawang Naval Base, built between the 1920s and 1930s as part of Britain’s defence against threats in the Far East, was a strong magnet for large numbers of Malayalee workers. By 1960, approximately 5,000 Malayalees worked in the naval base dockyard, earning the base its nickname of ‘Little Kerala’. Malabaris too worked and lived in the naval base as well as in the surrounding areas at Sembawang. The expansive Sembawang Naval Base, spanning from Sembawang Road to Woodlands, offered administrative and ship repair roles to Malabaris. Working alongside Malayalees, Indians, Singaporeans, Malayan, and Hong Kong workers, the Malabaris held positions such as engineers, mechanics, and general workers across specialised departments including metal works.

Apart from the naval base, Malabaris lived and worked in Sembawang Village, which was established in the late 1920s at the 14th milestone of Sembawang Road. By the 1960s, the village had a population of 1,200 residents, amongst them Malabari families and shops servicing the nearby naval base.

While earlier generations of Malabaris set up homes in Sembawang, Woodlands, Kranji, Seletar, Changi, and in other areas like Toa Payoh, Beach Road, Arab Street, Jalan Besar, Desker Road and Tanjong Pagar, today Malabaris can be found scattered in many other parts of Singapore.